The Condor

Of all America's national treasures, California condors are without a doubt the ugliest. Unlike Mount Rushmore, or a herd of bison moving through Yellowstone, or a San Diegan taquería, condors are an acquired flavor. Yet underneath their revolting appearance hides one of America's greatest success stories.

They are objectively "gross", at least superficially: dusty black birds with bald, wrinkled heads and a tendency to urinate onto their own legs. They're large, but not menacing. When feeding, they dip their naked faces into decomposing corpses and pull out tiny bits of flesh with their weak jaws. They don't even have cool talons. As scavengers, condors don't really attack or defend much of anything, they make a living alternating between soaring at 15,000 feet and snacking on variably decomposed carcasses.

But even though they are a perfectly apt symbol of death and decay, the reason every American should treasure their existence is truly beautiful. Condors aren't exactly the most glorious emblem of our nation, but they do represent America's uniquely wonderful potential. Sort like if you ran into Gary Busey at the Grand Canyon, or a saw Statue of Liberty made out of gruyère cheese.

Their claim to fame is an incredible close brush with extinction, remarkable in an animals with ten foot wingspans who evolved to feast on woolly mammoths carcasses. Back in prehistoric North America, condor populations filled the skies across the entire continent, but were slowly whittled down to just 22 birds by the 1980's, sequestered in little pockets of the Southwest.

Luckily for them, conservation at that time was on a hot streak. Captain Planet was kicking ass, and a new crop of kids was growing up not even knowing bald eagles had ever been endangered. With the bold initiatives of serious conservationists, the federal government was convinced to step in and save the California condors.

Wildlife agents were dispatched to the range, and the last wild birds were taken into US custody for safekeeping.

Once the birds got frisky in captivity, the project turned out to be massively successful. Breeding programs led to hundreds of successful hatchings, and within a few years condors were reintroduced to wild places to spread their wings again.

But arguably more successful was the public education arm of the operation. A harrowing escape from extinction is an all time great story, and an entire generation of animal nerds now idolized condors. These (superficially) ugly animals became one of the sexiest conservation projects in town.

Today the condor population is 25 times bigger than when I was born (coincidentally, also naked and covered in blood).

One of the most magical things about my childhood was that I grew up almost literally in the shadow of the San Diego Zoo. Which meant zoo camp every summer, which meant plenty of condor Kool-Aid, and I guzzled it down. I dreamed of the day when I'd get my shot at the glory of animal conservation.

It took years of studying, volunteering, and working my way up to get into the Biz. But finally, when I was in vet school, I got my chance. I'd be working with California condors. It was surreal!

I was in the backseat of a pickup truck, bouncing along as an intern with a wildlife medicine program. We got to a large clearing in the woods, where several enormous aviaries had been constructed.

When we parked, I could see it there, perched on a high wooden platform. A real life, honest-to-goodness, critically endangered California condor. And I was going in there with it!

The bird tracked our movements with aloof skepticism.

So... and I know this seems crazy, but how it works is that the interns go in and flush the birds off the platforms. These aviaries, although gigantic, aren't actually big enough for flying condors to maneuver within. If you knock them off their perch, they can really only land in a certain spot at the other end of the pen. That's where the actual skilled professionals get a handle on them and perform the necessary medical care.

I was not one of the experienced professionals.

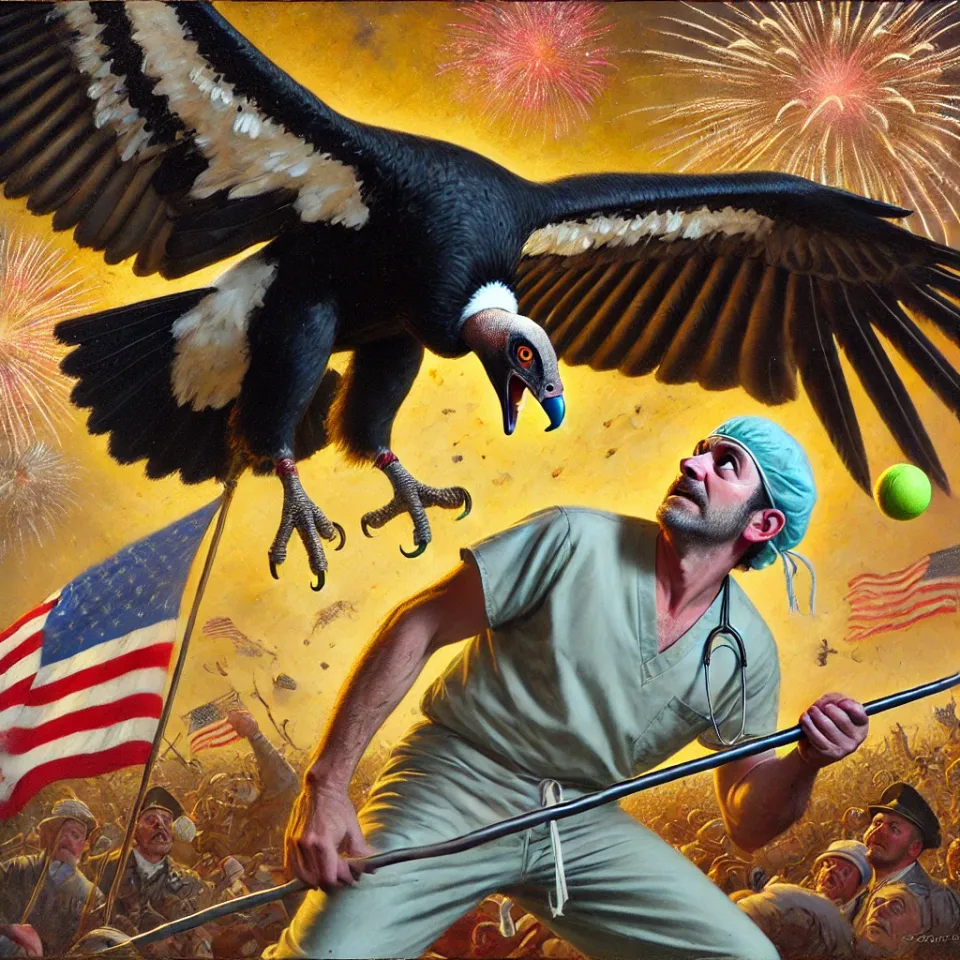

So I was handed a pole, the tip of which was covered with a tennis ball, for safety. And I appreciated that, because it was the only piece of safety equipment in sight. No climbing equipment or helmet was mentioned before I was pushed into the aviary and told to start climbing.

Sure! I'll whack a childhood symbol of national pride with a long bat! Whatever it takes to serve the cause!

Inside the aviary, I could see in detail the splintered logs and rusty nails of the perch, which I assume had been constructed in great haste and at maximum cost efficiency.

The condor, apparently familiar with this whole drill, held its ground and watched to see if it might be one of those lucky days when the intern slips off.

I got within striking distance. The post swayed a little.

I looked up into its eyes. One of my childhood idols now appeared mildly annoyed with me, a deranged lunatic invading its home with some bizarre piece of sporting equipment. And for what? If this psycho got any closer, it would have to fly off to another splintery post.

Why go through all the trouble? What was the point?

I shimmied upward and aimed my metal pole straight at the condor's cloaca, of which I had a direct and unobstructed view. With one precise tap, the bird–miffed at the whole indignity–leapt off, leaving the platform swaying unnervingly. I held on for dear life and watched its majestic wings spread out to full breadth, gliding the prehistoric creature to the other end of the aviary.

I consider my actions that day unconscionably rude. I'd never allow that behavior from a five year old. But on the other hand, sometimes this is how things works. Conservation is really just medical care for an entire species, and medicine isn't always pretty. There are tradeoffs and unintended consequences and ethics-wrenching decisions to be made.

But at this scale, it's truly extraordinary: an entire network of people and ideas that have achieved the unprecedented. There's nothing else like it in the entire history of the world. An animal, an entire species resting on the very edge of disappearance gently revived through the remarkable efforts of humanity.

Okay, so not always super gently. I mean–I tried, but they're big birds and it's tough wielding a ten foot pole when you're straddling a splintery telephone pole. Sometimes you get a few scrapes and while bopping a large, flying scavenger on your way to a species-saving omelette.

It may be a little ugly on the surface, but deep down, it's beautiful.

Just like a condor.

Please consider a donation to the Ventana Wildlife Society to support California condor conservation efforts, or check out one of the condor webcam to see these repulsive animals for yourself. Thanks for reading.

Comments ()