Same as it Ever Was

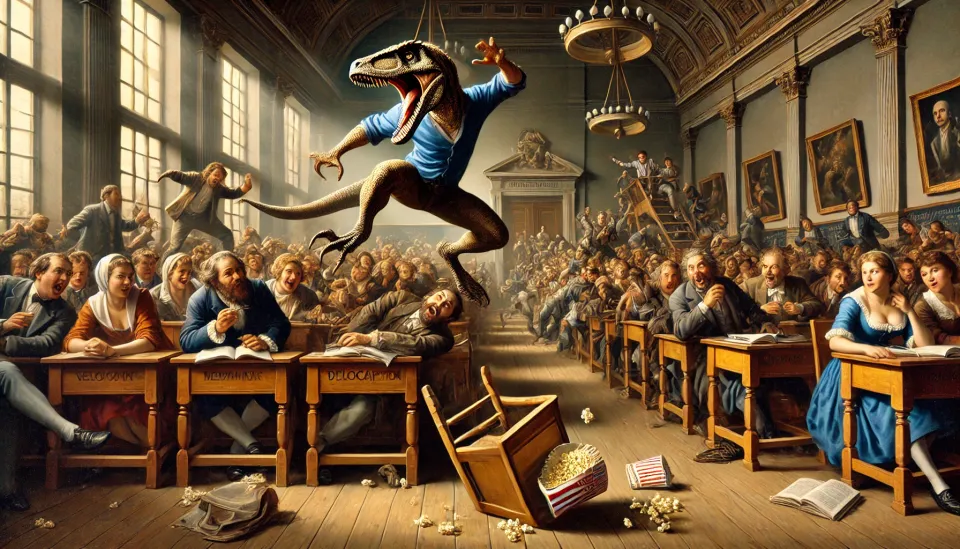

A couple of months after starting vet school, one of my classmates spam-emailed the whole student body. There was no message, just a Photoshopped image of me posing as a velociraptor, next to the bold title “Jurassic Park Live, this Friday!”. This was a pretty funny joke email, something our class had firmly established in the first few months of school together. Hanging out with hundreds of animal nerds was exciting, and those of us inclined to be goofballs had a hard time containing it. I guess I was talking about dinosaurs a lot.

I thought it was a good idea. I immediately hit ‘reply all’ and gave them a room number and a time to show up. That Friday night, I streamed a bootlegged version of the film on our classroom’s giant projector screen and acted out as many dinosaur scenes as I possibly could (including the terrifying kitchen scene, during which I leapt irresponsibly over the heads of several students in a feat of athleticism of which I am no longer capable).

In most social settings, pantomiming as a velociraptor would be considered socially unacceptable behavior. But in vet school, I was lucky to be around a bunch of other doofuses. We spent four years together goofing off. We produced a series of music videos,¹ threw a mustache-based fundraiser for homeless pets, and built a life-sized sauropod float for the university parade. We learned a lot too, but balanced every group study session with plenty of jokes.

Reflecting on this recently, I realized how happy being the class clown made me, especially in the niche world of animal science humor. Vet school was a lot of work. I leaned on my classmates all the time, whether for help understanding equine renal physiology or figuring out which corner of the sprawling campus to show up for sheep restraint lab on time. I felt like flinging myself off a desk in a screeching raptor attack was the least I could do to pay them back.

I had been drawing cartoons for years already, and I started putting them in the vet school newspaper, eventually taking over as the editor in chief and recruiting fellow doofuses to contribute. We also made The Office parodies, interviewed an anthropomorphized Anthrax, and submitted a spoof vet school rap video to a local film competition (the crickets seemed to like it). When we graduated, my classmates asked me to deliver a commencement speech. I deferred any dinosaur-based acrobatics due to the billowing gown.

A brutal rotating internship, followed by a “real job” and the sprouting of a new family left me with little time or energy for pointless endeavors. Eleven years after graduation, I’d been focusing on building the knowledge and serious skills of a mature clinician. But in the back of my mind, I was always haunted by a soft, sweet calling. Fart noises. I wanted to goof off. Not to shoot spit wads, not to be nasty and break down connections with my peers, just to have fun with them.

Humor, as it turns out, isn’t just fool’s play. It has deep biological origins, theorized to have evolved as a way to reassure a group of skittish primates that they are, in fact, going to be okay. Individuals with the skill to recognize something as funny play a crucial role in society. Humor is a multifaceted, subtle and rich behavioral display. It’s a vital social connection. Did you know there are at least 20 different types of human smiles? We are built, much more so than any other animal, to be funny. I know pugs seem like they’re laughing, but they’re actually just struggling to breathe. Humor is a human specialty. We need it as an antidote for our anxieties.

About a year ago, I read Steven Pressfield’s book The War of Art, and a lightbulb went off. I realized that I had something to contribute to the veterinary community without specializing in an established subdiscipline. I thought having extra letters after my name was necessary to speak to my colleagues. I had forgotten what was so fun and useful about my veterinary school days.

So I got back in the habit of taking funny stuff seriously. I rekindled my cartoons, publishing a monthly feature in Veterinary Practice News (and submitted non-veterinary ones to The New Yorker). I launched a blog to tackle the important issues being ignored by the mainstream veterinary media, such as Chihuahua Denial Syndrome.

The response has been overwhelming. Several people have laughed. I’ve been invited on a few podcasts. There’s been interest in creating workshops for veterinarians, teaching them the importance and technique of humor, both as a tool for clinical communication and as a stress relief strategy. This journey has both reinvigorated my love for the veterinary community and alleviated the intense itch of my soul to bring forth art into the world (let’s call it “creative pruritus”). I’ve connected with others: veterinarians, scientists, cartoonists, innovators and fellow creators who want to see human and animal society flourish together. And I haven’t even needed to turn myself into a screeching velociraptor in public (yet).

- This sketch, in my opinion, is the finest work we ever did. Courtesy of the brilliant performance of a current veterinary cardiologist.

Comments ()