Conflict of Interests

I went on a date the other night, but not with my wife. It did feel a bit wrong in some ways, but nobody (her included) seemed to mind too much, so I just went along with it.

It was a nice restaurant. Unusually for an evening like this, I wasn't worried about making a good impression. I did put on a new button up shirt (but someone had to remind me that the price tag was dangling out the back). We had a nice cut of steak, a $12 glass of wine, and creme brûlée for desert. Best part? My date paid for everything!

At the end of the night, there was something special to look forward to. Not a brief moment of satisfaction, but a lasting treasure. A gift that would, in fact, keep on giving. My generous date had given me one hour of continuing education credit (CE). The next time my professional license came up for renewal, I would be grateful for this evening.

It truly is a privilege to be wined and dined by a pharmaceutical company. But for all the perks, I'd have a hard time without that CE. The fancy food, the premium cocktails, all the tasteful decorations and charming conversation by attractively-dressed sales reps, it all would feel so cheap and insincere if it weren't for that little hour of CE. That's what makes it juuuuuust pass muster as an honest act by a medical professional.

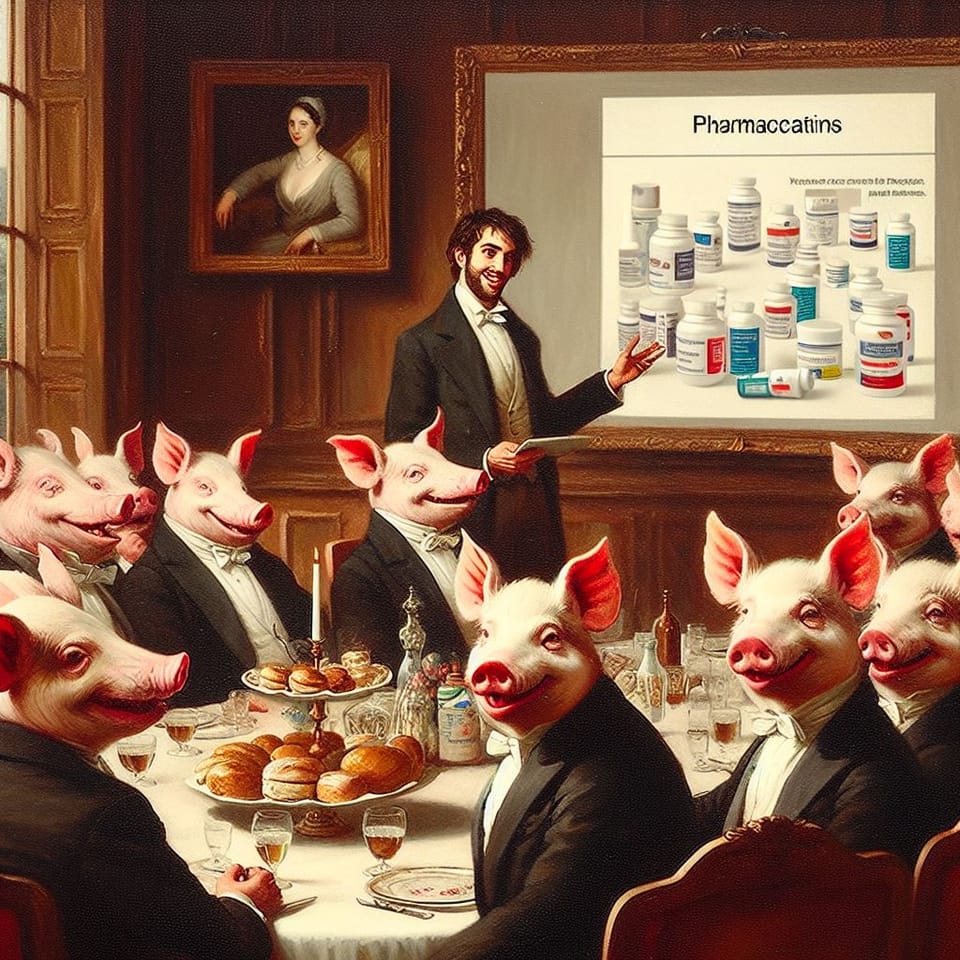

And boy, do they know it! They want you so badly. They thrust that CE on you like a promise of undying commitment from an enraptured young lover. Before you know it, you're eating out of their hand like a contented pig in a trough, happily jettisoning any erstwhile scruples you may have had about the slickness of your date's marketing material.

That hour of CE you're choking your qualms down for is something you need every year to maintain your professional license. Minimum requirements vary, but you're always on the lookout for the opportunity to snag some hours. Ostensibly, the state boards use CE mandates to ensure that licensees maintain current scientific knowledge. But truth be told, after the thousands of hours of lectures completed to gain that license in the first place, it's kinda hard to convince people to go sit through another hour of renal physiology. The trap must be pretty heavily baited.

It's tragically unfortunate that other options to stay up to date aren't incentivized. For example: let's say I plan and implement a clinical trial of a novel therapy in veterinary medicine, all on my own. I endure countless hours of study design, literature search, manuscript preparation, peer review and revision, and finally succeed in bringing a meaningful scientific paper to my field. That would net me zero hours of CE.

Or let's say I write an evidence-based article for a trade magazine about a current issue that is highly relevant to the majority of my professional colleagues. Which would require not only the hours of literature review, but also thinking broadly about the scope of practice across the country and a strategy for effective communication with an audience of my peers. Also, zero hours. Zip. Nada. I might as well get a light chicken gravy for all the work I'm putting in.

There are things I can do for CE besides eat steak, however. Suppose I subscribe to a leading scientific journal for a year, read every article therein, and consider all the clinical implications and study design limitations. Well now at least, I'm getting somewhere. I'd get exactly one hour of CE for that. Oh, and if I just toss the journal in the recycling bin every month without reading a single word? Yeah, I still get that same hour.

But sit in a warmly-lit ballroom, sip a full-bodied red from those thin crystal glasses we have at home because I accidentally break them, and suffer through a little small talk, and you get a full hour, sometimes 1.5, of precious CE. The meal is great, but would I really be there without that certificate of attendance dangling in front of me? Doubtful. I'll give in for the same reason my parents did when I begged for them to let me watch certain TV shows, it's educational!¹

Something about this kind of information tastes funny, though. Preliminary data are teased as "promising". Squishy, non-falsifiable are sprinkled in to make the whole thing go down smoothly. Rigorous peer review, this ain't. My skeptical bona fides shudder, embarassed at the thought that this scene is passing as real science. It's like learning about nutrition from the Cocoa Puffs commercial while watching Sesame Street.²

So yeah, "industry-funded tart" could describe more than just the desserts at these dinners. But then again, I'm not necessarily pining for the disintegration of the pharmaceutical companies. I do use drugs to treat patients. And I want new ones. I want a treatment for kittens with FIP. I want a better treatment for puppies with parvo. I want Big Pharma to keep investing the massive amounts of money it takes to invent new medical therapies.

If I can quibble, it might be ideal to just do the science. Just conduct the studies, submit the research for peer review, and keep investigating the treatment/drug/device/supplement/nosode/whatever in a variety of ways until most people evaluating the body of evidence seem to think it actually works. Then approve it for mass market. That would be a pretty good system.

But unfortunately it's a lot cheaper for a giant conglomerate to take hundreds of small groups of medical professionals out to fancy dinners and tell them that a small, tightly controlled efficacy trial proves their product works in the real world. And call that educational. After all, they've got the CE.

- Disturbingly, my son has now independently discovered this trick.

- Kids, there used to be this thing called TV. It would just play what was on a channel, you couldn't pause it when you had to pee. And there were commercials, so every time you got excited about the story, you were blasted with images of ecstatic kids mainlining sugar and enveloped in gigantic plastic toys. Seems crazy, I know. But that accounts for at least 40% of how millennials interact with reality.

Comments ()